Robert McNamara was a product of the so-called greatest generation, who believed in his place in the world. The boomers challenged him for lying about Vietnam and for his contribution to the military-industrial complex. And then the boomers voted for Trump. So who’s making America great, again?

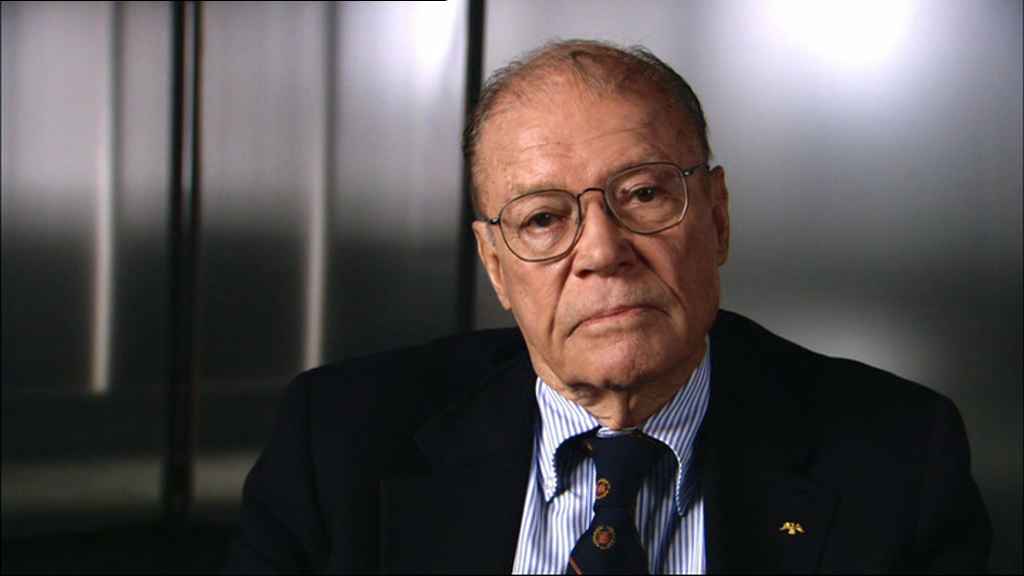

Did the twentieth century offer any poetry finer than a standardized test? Surely all those bubbled-in letters spell out something, but multiple choice itself is a love language. Plaintively, with each whirl of a No. 2 pencil, we plead that those letters will trace a path to the perfect score, to the perfect job, and to one perfect nation under God, indivisible as helmed by the Best and the Brightest — by intrepid men who bubbled impeccably. In his critically-acclaimed 2003 documentary, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, director Errol Morris interviews one such man who climbed the rungs of standardized testing into power. In his capacity as Secretary of Defense to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, McNamara was a severely gifted number-cruncher who escalated American military involvement in the Vietnam War even as he knew that it was unwinnable — a fact that he denied repeatedly, until the publication of the Pentagon Papers proved he had known all along. The film was released just as the coalition invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were descending into a Vietnam-like quagmire, making McNamara a timely interview subject.

It seems doubly prophetic that the film was released in 2003. This was the same year Facebook launched — and the internet began its stranglehold on our public, private, and political lives. While McNamara never digitally ranked the university’s hottest women during his own time at Harvard, as Zuckerberg notoriously did, he did help integrate IBM into global warfare during his time as an analyst in the Pacific theater during WWII and while Secretary of Defense to Kennedy and Johnson during the Vietnam War. Today, the automated war machine is something more subtle, as Facebook allows bad actors — whether state leaders or individuals — to promote propaganda and lies, and even help throw a presidential election.

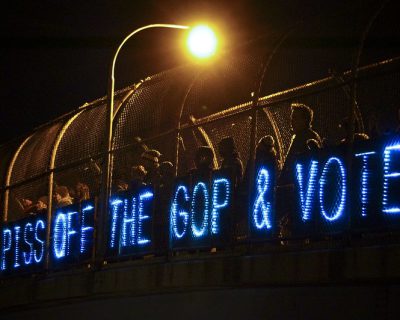

Morris, a baby boomer, engages McNamara in a deeply disturbing conversation about what the latter’s generation left Morris’s to sift through. As a millennial, when I first saw the movie in 2003, I felt I was watching the good guy from the generation that brought us Woodstock go after the bad man who brought us napalm. Today, I cannot say I look at the baby boomers as a merry band of Robin Hood types who sought to rescue the nation from the military-industrial complex. The 16 years since the documentary have seen the rise of one particular baby boomer who is, in many ways, antithetical to both McNamara and Morris. On the one hand, Donald Trump is nothing like my childhood idealization of my parents’ generation, protesting war and burning bras. On the other, Trump is nothing like McNamara: he is the wily byproduct of outer-borough nepotism who defies all statistical analysis. Watching The Fog Of War in 2019 almost made me nostalgic for what I now realize was a sense of progress that I had in 2003. It made me wonder what I have learned as the lofty aspirations of the Great Society have degenerated into the bitter pandemonium of Making America Great Again.

I offer — it seems appropriate — eleven lessons:

The fog of institutional faith rolls in before the fog of war

A little background: during World War One, the U.S. Army administered IQ tests, which begat the S.A.T., which begat the need for rudimentary computers to analyze the results, which begat IBM government contracts, which begat a bureaucracy primed for battle by December, 1941. This automated war machine had previously been marketed to America as a political platform to better manage America — the New Deal. The IBM punch card led the charge into the theater of war; attendant propaganda shorthanded a push for achievement. Science education would win the Cold War! The best and the brightest would protect us from falling dominoes in Southeast Asia! A moonshot could redeem humanity! Before he conveyed this militarized optimism, McNamara tested his way from UC Berkeley to Harvard Business School to celebrated Army analyst in the Pacific Theater of World War Two, a mascot for the meritocracy. Why listen to a damn thing he says? Well, look at those test scores!

Nothing lends political credibility quite like the private sector

Robert McNamara was the C.E.O. of Ford Motor Company when John F. Kennedy tapped him for the position of Secretary of Defense. In the United States, shaped by the Protestant work ethic, a rich person is by definition considered to be a smart person. In Fog of War, Morris shows archival footage of journalists ingratiating themselves to McNamara by complimenting him on his intelligence; during the 2016 presidential election campaign, the media reported on Donald Trump’s private plane, his luxurious residential properties, his hotels, and his private golf courses. In The Fog of War, as McNamara accepts the cabinet position, Kennedy says that McNamara has chosen to serve his country at “great personal sacrifice” — which is code for giving up the extremely generous salary of a C.E.O. in the private sector in exchange for a civil servant’s salary.

The Greatest Generation™ and the baby boomers double-teamed successive generations

The Vietnam War inspired a libertarian insurgency on the right and a counterculture from the left, with adherents to both questioning the enormous role big government (as the right calls it) and the military-industrial complex (as the left refers to it) played in policy implementation that affects our lives. This wide loss of faith in the government saw its first expression in anti-war demonstrators chanting “hey, hey, L.B.J., how many kids have you killed today?” — but Watergate dealt the death blow. The revelations that came out during the impeachment hearings into the Nixon presidency alienated Americans across the political spectrum, and on both sides of the generation gap. In 2016, the same generation that drove Nixon out of office voted Trump in. In a New York Times op-ed about baby boomers who voted for Trump, the writer and activist Astra Taylor suggests we “call it the coming gerontocracy.” The hippies told us never to trust anyone over 30; frankly, I wouldn’t trust anyone already receiving Medicare or Social Security — they’ll kick the ladder right out from under you.

America remains a sucker for postcolonial civil conflict in countries it scarcely understands

Near the end of The Fog of War, McNamara talks of dining with his North Vietnamese counterpart in 1995, who told him, “Mr. McNamara, you must never have read a history book. If you had, you’d know that we weren’t pawns…Don’t you understand that we have been fighting the Chinese for 1,000 years? We were fighting for our independence and were determined to do so to the last man.” As McNamara recollects this tense conversation, it’s almost like he’s saying, Right but you said that wouldn’t be on the test. While McNamara openly — astonishingly — concedes his ignorance, he refuses to concede his mode of thinking had been wrong, or that “each of us could have achieved our objectives without the terrible loss of life.” On October 6, Trump abruptly announced that he was pulling U.S. military support out of the Kurdish-held territory northeast Syria, leaving the Kurds — who had sacrificed more than 11,000 combatants in the fight against ISIS — extremely vulnerable to a massacre at the hands of Turkish forces, who were poised to cross the border. Supposedly to preempt this from happening, Trump wrote a widely-circulated (and widely-ridiculed) letter to Turkey’s President Erdogan. “Let’s make a deal! You don’t want to be responsible for slaughtering thousands of people, and I don’t want to be responsible for destroying the Turkish economy…Don’t be a tough guy. Don’t be a fool!” Erdogan, according to several reports, promptly threw Trump’s letter into the garbage.

Statistics are amoral

The most visually eloquent moment of Morris’ documentary comes as McNamara explains the impact of the U.S. firebombing 67 Japanese cities during the Second World War, while, in the accompanying footage, numbers are shown raining down from bombardiers. Stomach-churning statistics follow, unmistakable as atrocities — in some Japanese cities, up to 90 percent of the population was killed by U.S. aerial bombardments. McNamara concedes as much, but he also justifies the bombings. The war between the U.S. and Japan, he explains, was “one of the most brutal in history.” The Americans could not afford to lose, and that was why he “didn’t fault” Truman for using the atomic bomb. McNamara asserts that General Curtis LeMay would have been prosecuted as a war criminal if he had lost the war in the Pacific, just as he (McNamara) would have been prosecuted had the U.S. lost the war in Vietnam.

After World War Two, discharged from the U.S. military, McNamara went to work for Ford Motors. There he crunched the numbers again and mandated that all the company’s cars must have seat belts. He applied the same logic that justified the deaths of 2 million Japanese civilians to the saving of 15,000 American lives annually — according to the National Transportation Board.

Trump is cagier with numbers; we haven’t even seen his tax returns. But we do know this: he has 65.9 million Twitter followers.

We’ve gone from fireside chats to a dumpster fire — but at least there’s no draft!

For good reason, Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s is the subject of much discussion these days: polarized political ideologies, hysteria, and a U.S. president who won’t shut up on that newfangled media outlet called Twitter. The Great Depression required large-scale political and economic solutions. After the Second World War, the G.I. Bill allowed (white) men to receive a free college education. In today’s privatized, post-Raegan, gig economy hell, apparently 70 percent of us want universal healthcare and 58 percent want debt-free education, but far fewer Americans—I’m hazarding a guess here—pine for a government capable of sending us to certain death in Guam. The Greatest Generation™ may have basked in the glow of a welfare state, but it also tolerated the draft and a powerful government that operated far away from a free press with the likes of Seymour Hersh poking around its files and exposing war crimes like My Lai. Given that many Americans want a government that provides us with more, we also need to be mindful of what such a powerful government can take from us.

The Space Race might be over, but we found a black hole!

Fittingly, one of the bright spots of the Trump era has been a literal black hole: in April, the very first image of one was captured by an international team. Meanwhile, the American century’s certainty of measurable progress has collapsed; we are a dying star and this black hole has a name: the algorithm. All the numbers, all the metrics have been automated and programmed to produce more and more data and metadata, so that discernible political reality has collapsed under its own weight, and space-time warps into phenomena like Pizzagate. On December 4, 2016, a man fired multiple rounds of ammo into Comet Ping Pong, a D.C. pizza joint thinking he was busting up a sex-trafficking ring run by Hilary Clinton. This rumor had been spread as “news” by Twitter bots and Trump supporters, much in the same way the Obama birther “movement” was spawned. Uncannily, in NASA illustrations, the silhouette of a star-death is orange and flailing.

No one is at the wheel anymore

Our economic reality is the same: our war machine has collapsed into a Ponzi scheme of a service economy. Corporations that boast of high valuations do not created anything, post no profits, and offer employees few benefits. As Rick Wartzman, author of The End Of Loyalty: The Rise And Fall Of Good Jobs In America, pointed out, “We’re now at a point where fewer than 7 percent of private sector workers are unionized in this country. And it’s just clearly not enough to have the kind of collective voice and countervailing power against corporate power that, again, was able to lift wages and benefits for all folks, not only those carrying union cards but other blue-collar workers and even white-collar workers in the past.” Fewer Americans have health insurance with every passing year, yet we have apps to manage apps. The cruelest irony is this: the data sucks! Remember the 2016 electoral polls results that showed Hillary Clinton’s victory was a dead certainty?

Still, we remain in thrall to irrelevant figures — like the stock market — and use such indexes as magical thinking to ward off evil premonitions of decline and fall. Reporting on a paper the Fed published earlier this year, Forbes, not exactly known as a bastion of Sanders supporters, published an article titled with Trumpian hyperbole, “America’s Humongous Wealth Gap Is Widening Further.” It gave the following statistics:

In 2018, the richest 10 percent held 70 percent of total household wealth, up from 60 percent in 1989. The share funneled to the top 1 percent jumped to 32 percent last year from 23 percent in 1989. ‘The increase in the wealth share of the top 10 percent came at the expense of households in the 50th to 90th percentiles of the wealth distribution.’ Their share dropped to 29 percent from over the same period. The bottom 50 percent saw essentially zero net gains in wealth over those 30 years, driving their already meager share of total wealth down to just 1 percent from 4 percent.

But who cares when the DOW is up over 27,000? McNamara’s tyranny of numbers is complete.

Keep it casual!

Though an egghead as surely as he breathed, McNamara kept a common man image close at hand. The very same meritocracy that enabled his rise, ensured he could always do so. He could always claim, no matter how many diplomas he’d earned, no matter how many companies he’d run, that he was a middle-class Irish striver and a family man. Today we have Trump who is, as Fran Lebowitz deliciously put it, “a poor person’s idea of a rich man” — from the Fifth Ave apartment that looks like Versailles vomited to the McDonald’s catering for Clemson’s triumphant football team at the White House. Populism is always essential in the American political arena, as the imminent spectacle of all 19 Democratic candidates chowing down on corn dogs across Iowa soon will prove.

The meritocracy was a Western

The American meritocracy has closed, like the American frontier. Much like the frontier, the illusion of accessibility was the most potent part of its myth of inevitable progress and increase. The barriers, too, were the same: race, class, gender. As with a Western, when you step back a bit, you may ask, why on earth is this our chosen narrative of progress? What is the enduring appeal of genocide and discrimination in this country? Yet, there is an almost sweet naïveté in the notion that something as simple as a test could identify all our future leaders from all walks of life! Similarly, there is a grand romance to thinking an empty continent simply awaited discovery and settlement! But the problem is the continent was not empty, and not everyone could take that test, let alone access the tools to excel at it. And the results of the test themselves were impoverished scraps of data that correlated to achievement insofar as they granted that selfsame access. Nothing succeeds like success!

R.I.P. public service

The ideal of civil service, as illustrated by Kennedy’s founding of the Peace Corps or Carnegie’s philanthropy, is dead. The Trump administration’s scandals, shameless profiteering from the private sector, and virulent partisan politics have painfully gutted agencies ranging from the foreign service to the Department of Justice. In her recent testimony to Congress over influence-peddling in Ukraine, former U.S. ambassador Marie Yovanovitch said:

Before I close, I must share the deep disappointment and dismay I have felt as these events have unfolded…Today, we see the State Department attacked and hollowed out from within. State Department leadership, with Congress, needs to take action now to defend this great institution, and its thousands of loyal and effective employees.

She added that she feared “harm will come when bad actors in countries beyond Ukraine see how easy it is to use fiction and innuendo to manipulate our system.” The integrity of institutions has eroded at a terrifying pace; and that wealth of experience and culture of service cannot simply be rebooted in an election cycle or two. The sort of service to mourn is not the type exemplified by McNamara — an executive who traded outstanding profits for unthinkable power — but that of the 2.79 million civil servants who get out of bed, make the federal government run, and will never have an Oscar-winning documentary that motes they “sacrified” a big corporate salary.

Today marks the release date for Errol Morris’ newest political documentary, American Dharma. His subject this time is another creature of his times — Steve Bannon. As the historical narrative passes over the event horizon and into the black hole of Twitter, I am reminded of that fabled ghost in the American propaganda machine — the myth of American exceptionalism. Morris’s movie makes the following thesis statement on the origins of McNamara’s power and how it tied into his own sense of exceptionalism: he was the very embodiment of the American meritocracy. Meritocracy, this vaunted bubbler would have us believe, identified the talent that enabled America’s successful prosecution of World War Two; triumph in the Cold War; and stewardship of the Free World. As ludicrous as this sounds, the fact of the matter is, that I see how someone could have felt this way in the thick of it all. I see how someone might have taken a test, served in the Army, gone to college, gotten a job, bought a house, made a life, and felt pretty great about the whole system. Yet, in the thick of 2019, from my own considerably privileged perch, I don’t see how anyone could feel that sense of purpose and belonging from the service economy that isolates and social media that distorts — and I wonder what Gen Z will make of it all, another 16 years from now.